|

Day B10 - Highest

point of the canal

|

|

March 12,

2010

Castelnaudary to

Villefranche-de-Lauragais

16 miles

|

|

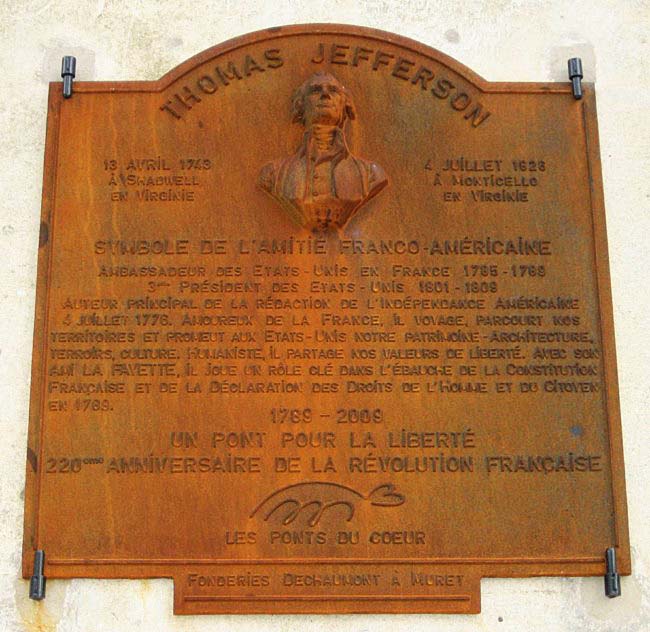

This is a 2009 plaque erected on the wall of one of the lockkeeper's cottages on the continental divide. Thomas Jefferson visited and studied the Canal du Midiin 1787 with a view to creating a similar canal between the Potomac and Erie rivers in the U.S. My translation* of the plaque reads as follows: Thomas Jefferson United States Ambassador to

France 1785-1789 Lover

of France, he journeyed through our territories and promoted to the

U.S. our heritage – architecture, lands, culture, humanism. He shared

our values of liberty. 1789 –2009 |

|

|

|

<<<

West to the Atlantic

East to the

Mediterranean >>>

A feeder

canal (above)

delivers water from the mountains to the Canal du Midi here, at the

Continental Divide.

At this very point, water on the left of the picture flows to the Atlantic, and water on the right towards the Mediterranean. Below, a sign identifies this as "The Parting of the Waters". |

|

|

|

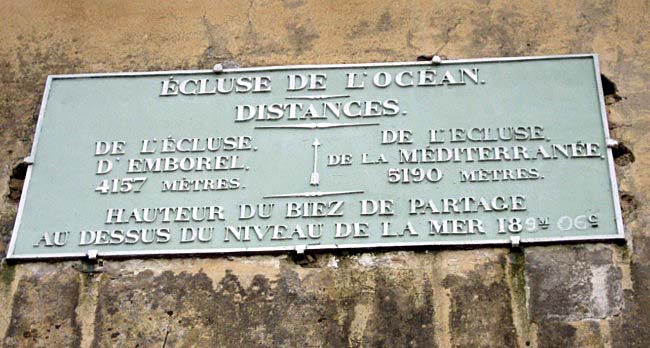

Left, the first lock "down" to

the Atlantic ("l'Ocean")

Right, the last lock "up"

from the Mediterranean

Plaques at all

locks indicate their elevation, and the distances to the adjacent locks.- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - There are 65 locks on the Canal du Midi, and 53 on the Canal latérale à la Garonne. In both cases, this is less than the original number. One reason, at least, is that water bridges now carry the canal over rivers, when formerly both canal and river had to be brought to the same height to allow boats to cross. Those intersections had sometimes required locks for the canal and dams for the rivers. |

I

arrived at Bram station in perfect time for my short ride to

Castelnaudary - the train was waiting. With the ticket office closed in

the early morning, I made sure I exactly followed the process explained

to me on Day B8.

I got to Castelnaudary station as early as 7.45 am, and it's just steps from the canal. It was a flying start to the day. Yesterday, I had worn seven layers of clothes on my torso, and been none too warm. Today's warming trend caused me to cut back to four layers. But, if the temperature did actually rise through the day, it wasn't all that noticeable. The headwind that's been so prevalent came back, and chilled away whatever warmth there might have been. There's some rain in the forecast, also, but I got Seattle-mist and Surrey-cloud instead. If you've wondered why the canal never freezes in these temperatures, well . . . it does. I saw ice stretching right across it in one section sheltered from the wind. Of course, boats would likely cut right through such a thin layer. But, then again, I haven't seen a single moving boat in all my approximaterly one hundred miles. I stayed on the canal for about eight miles straight this morning, and with mounting anticipation. That's because I would soon reach the continental divide, at 189 meters (620 ft), at which point the locks started their downward trend, just as expected. Moreover, on the stretch of canal between the last "Mediterranean-oriented" lock and the first "Atlantic-oriented" one, the water supply from the Black Mountains enters. Actually seeing this impressed me more than suggested by my pictures. On a particulate level (physics-speak), the thought of one particle of water entering the canal from the Black Mountains and turning towards the Mediterranean - while its immediate neighbor turns to the Atlantic, all by design - almost boggles the mind. Of

course, it was a brilliant inspiration to replenish the canal water

that runs to each coast with a supply drawn from a dam built many miles

away in the mountains and led here by its own canal. But, like an

engineer, imagine what it must have taken to assure success before the

massive earth-moving and lock-building project created the canal. They

had to know what amount of water was needed, a no-small feat, requiring

a knowledge of ground absorption, evaporation, lock usage, irrigation

draw, and lock leakage. They had to match this water need to the

cachment water that was available for the dam, and then design the dam

and its controls. They had to consider the impacts on rivers that ran

into the canal, or which used to be served by water now captured for

the canal. All this had to be known for drought as well as flood, and

everything in between. A whole range of hydraulic, but hand-powered,

controls had to be invented to make it all work.

They did all this without a single internal combustion engine or amp of electricity, using primitive surveying instruments, hand-written communications, and no computers. When they'd finished, they'd created a nearly 300-mile waterway that transformed south western France. Ducks and geese were plentiful, with the geese flying in and flying out almost like they were in a waterpark. Just one swan was also present. The

canal towpath had delightful variations today, all of them acceptable

for hiking but ever-changing for interest. There was a section of

blacktop. A section of gravel, some of it new and clearly a repair for

muddy patches. There was the usual hard dirt, and for a change some

grassy miles. On a lock's downside, the tow path is usually graded so

that hikers and bikers don't face a set of steps. I reach

each lock eagerly, and read the distance to the next, pausing to look

at the lock-keeper's cottage, and his yard. Dogs bark in the distance,

horses on nearby fields may bray, ducks quack, and geese squawk. Boats,

when I see them, are nearly all boarded up - as are restaurants. Humans

are rarely in sight.

It's fascinating to imagine the activity in summer. I've read that 50,000 boats are on the canal. Eventually, I needed to leave the canal for a few road miles into Avignonet Lauragais and then my destination of Villefranche de Lauragais. But, with a renewed headwind - the force of which was strongly communicated by frenetically-active wind turbines on a close-by ridge - I decided to make a real stop for lunch. It was pizza time, French-style. The crust was thin and crisp, the cheese bubbled, the onion nicely-brown, and Hobson ate a large one while chatting to the store owner. Feeling

revived, I also chatted to cabinet-maker Claude Thuriés. Claude has his

store and his workshop on the main street of Avignonet Lauragais, and

what marvelous furniture he makes. It's all done from solid wood, even

curved-sided pieces with scrolls. Words and my pictures do not do it

justice. If you are ever here, drop in on him.

It was a long day but with an early start. I was tired towards the end. The Hôtel du Lauragais has seen better days, but has a fine dining room with a roaring "walk-in" fireplace. It also has wifi, so I managed to upload this and previous days' reports. I also plan to connect with Jennifer by Skype when she gets home. Finding accommodation for tomorrow was its normal time-consuming challenge. It's a fairly comfortable two-day's hike to Toulouse now, but that's assisted by finding accommodation halfway between here and there. Using the Internet, I located a motel at Donneville, but the owner's French was totally beyond my comprehension. The solution, once I saw it, was to ask my current hotelier to make the reservation. Duh. |

|

|

|

| Start Intro Day B9 Day B11 |

| © 2010 - 2013 Daryl May |