|

Day B27 -

Mediterranean to Atlantic, done

|

|

March 30,

2010

Lesparre Médoc to Soulac-sur-Mer

19 miles

|

|

|

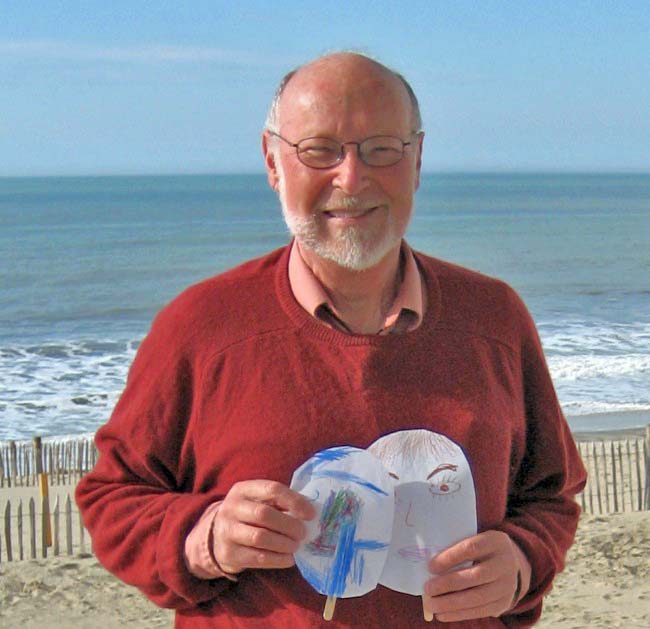

| Top,

my picture at Soulac-sur-Mer was taken on a calmer day than my actual

arrival day in heavy winds. I am posing with artwork by my

grandsons Steven and Wyatt, then 5 and 3 years old. Above, the Cordouan Lighthouse is visible from the Soulac beach at a distance of five miles The shot at the foot of the page was taken from a visiting boat (courtesy "Wikipedia free"). |

It took me

all day, but I finished the last day of my 19 miles with a

sense of achievement and of relief.

But the hike itself was quite dreadful. To get back to Lesparre to begin the hike to Soulac, I had a choice of two trains, one at 6.33 am and another at 11.40 am. The latter was too late, so I chose the one that was too early. Arriving at Lesparre at 6.50 am, it was dark - and with daylight-savings-time, it wouldn't be light until 8 am - even on a clear day. Well, it wasn't a clear day, and it started to rain. There was nowhere to stop for even a coffee and baguette. At best I could shelter from the rain under an awning - or I could walk. I walked. The rain got worse, and the grass verge got muddy. Moreover, it had lots of molehills - and into the mole-holes my boots descended. Then it got breezy, and later blustery. When daylight arrived, positively the only good thing about the situation was that I'd covered a couple of miles safely. I hoped the rain would subside as the day warmed, but it hardly warmed and the rain hardly eased at all. It took another three miles before there was any improvement. Having planned the day's route with Steve B, I swung onto a side road to Vensac which at least relieved traffic concerns, but then the rain resumed in full force, and I reckoned I'd better stay close to the bus route in case I called it a day. So I swung back to the main road. If

things weren't miserable enough already, there was worse to come. The

wind strengthened at about 11 am to what was assuredly gale force, and

it stayed at that strength for the rest of the day. When it rained,

there was no possibility of using the umbrella. It was hood-up and

head-down, lean forward and trudge. On any other day of this entire

hike, I would have run for cover. But not on the last day.

Eventually, the rain eased and sometimes stopped. But not the wind. Worse, for the last three miles it veered towards my front, and then the road swung left so I was headed right into it. When I reached the beach at Soulac, where there was nothing to break the force of the wind, breakers raced for the shore and the sea was muddy from churning up sand. The beachfront was quite deserted, and it was hard to keep on my feet. But nothing was going to stop me finishing now. Though the wind* made it a challenge, I swept my hand through the Atlantic surf, and the hike was done. * With the help of my friend, Steve B, who located historical weather data here, I was later able to quantify the windspeeds today, taking the average of the nearest four coastal weather stations. In the early afternoon, when I was reaching Soulac, winds averaged 74 km/h (46 mph) with gusts to 103 km/h (64 mph). Hiking without the backpack was essential today. With it, I couldn't have walked the distance in these winds. I haven't spoken about injuries recently. My battered big toe takes its daily hammering, and does not get worse, but it's painful. My toes are otherwise in reasonable shape, given that my bruised, black toenails will heal. I am pleasantly surprised by my ankles, which have stood up nicely. My right ankle used to roll easily - and once that started, the tendons stretched and then it rolled even more easily. That hasn't happened this hike, and though I would like to give credit to a few strengthening exercises, I am mystified. My arthritic right knee has occasionally scraped on itself, and given pain, but I seem to unconsciously avoid the maneuvers which cause that, or muscle development has helped. I am probably quite fit cardiovascularly now, a blessing and a reward for six to eight hours of vigorous exercise every day. I have two worries. My shoulders ache even without the pack, which brings to mind a rotator cuff injury from the last hike, and the operation which took months of recovery. I hope I haven't messed that up. Also, I too-often feel strain at the site of my first (and only) hernia operation, and I really don't want a second. The backpack weight can't help. In today's conditions, I don't think I could have finished with the backpack on. So, if Hobson hobbles home now, it's as well that's it's over while he still can. And that's a thought to keep firmly in mind for the future. After a while, a completed hike takes on the glow from rose-colored spectacles. I have asked Jennifer to remind me about my call after that terrible first day, when five miles brought me to my knees and I told her I didn't think I could do this hike. I think, now, that I was suffering the side-effects of antibiotics. But that confession is still part of the picture. I also don't want to pretend for a moment that this hike - or my previous ones - are in any way remarkable. Younger and even older folks do these hikes easily and faster and probably more often than me. I can only speak for myself, and say that these hikes are the hardest of my own physical challenges.

When

I finally reached the beach at Soulac-sur-mer, I was drained of energy.

But after the shortest of rests, my energy was replenished by a sense

of accomplishment. I had walked 375 miles in 27 days, averaging 14

miles (22 km) a day. More importantly, I'd seen an untold number of

beautiful sights and experienced a new (to me) culture and language,

and wonderfully-welcoming people.

I

had explored my innermost thoughts. It is what a solo hike invites, but

they can still be elusive. I thought about blessings and misfortune, about youth and age, about

loved ones lost and loved ones that can still come home, and what can

yet be, and what can't. We could take a boat ride,"

said Hobson. I

told Hobson that the boat tour runs only in summer. And, no, we're not

going to "borrow" a boat, and land on the rocks in raging seas and a

fearsome tide to end up in the hands of St. Peter or the gendarmes. "If it's St. Peter, we're

doomed," said Hobson. "I'd rather take my chance in a French prison."

"The

water temperature is up to 6 degC," Hobson added, as if precision could

make the impossible possible. "It's exactly 5.3 miles on a bearing of

339 deg." I told Hobson we weren't going

to swim, and he acknowledged defeat with a sigh. But not for a moment

did we want to swim anyway. It just wasn't the time of year

for a

foolhardy shot at fulfilling this particular dream. With

that remark, Hobson and I

knew we'd simultaneously reached a face-saving decision:

"If the King never visited, then neither shall we!" Dreams, you see, do not always come true. If they did, there would be no dreams. We must save some for the future to keep our dreams alive. And, with the lighthouse no more than a beckoning column on the horizon, Hobson ended his hike having reached the Atlantic coast. And so did I. |

|

The

Cordouan Lighthouse

For those interested in the

significance of the Cordouan Lighthouse,

I've prepared this footnote.

The Cordouan Lighthouse sits at the mouth of the Gironde estuary, out at sea but easily visible from Soulac. In factual terms, it's the world's 12th tallest lighthouse at 223 ft or 68 m, not bad for a structure built 1584-1611. (It was heightened slightly in 1788-1789, but without reworking the pre-existing foundations and superstructure.) The importance of its location can be gauged from the fact that there have been lighthouses on the same site since the year 880, though then lit only by a fire and visible for a very short distance. In its 1584 recreation, Cordouan was designed and built by Louis de Foix. The purpose was the safe export of Bordeaux wines. As Wikipedia reports . . . "De Foix first built a round base 135 feet in diameter and 8 feet high to take the onslaught of the waves. Within it was a cavity 20 feet square for storing water and other supplies. Above it were constructed four storeys of diminishing size. The ground floor consisted of a circular tower 50 feet in diameter, with apartments for four keepers around its inner wall. Inthe centre was richly decorated entrance hall 22 feet square and 20 feet high. "The second storey was the King's Apartment, consisting of a drawing room, ante-room and a number of closets. The third storey was a chapel with a domed roof notable for the beauty of its mosaic. Above this was a secondary lantern, and above that the Lantern itself. This was 162 feet above the sea and visible 5–6 miles away, the original light being provided by burning oak chips in a metal container. "Throughout

the building, de Foix took as much trouble with the decor as with the

durability of the building, and on every floor was a profusion of gilt,

carved work, elegantly arched doorways and statuary." Stained glass windows in the chapel, pictures of the King's apartment, and views from atop, are shown here, where it's reported that "most of the stones [that] make up the entire thickness of the tower . . . are assembled in such a precise fashion that it is impossible to slide the blade of a knife between the joints". The King's

quarters allow the Cordouan to be called the "King of lighthouses, and

the lighthouse of Kings".

But

perhaps it is the light itself that makes Cordouan the world's most

historically-significant lighthouse. For here, Augustin-Jean Fresnel

(1788-1827) pioneered a lens that made lighthouses what they are today.

Instead of using just mirrors to amplify the light source, Fresnel

developed a new lens system that still bears his name. It completely

changed the way that lighthouses beamed their lights. As The Times reported,

"the Fresnel lens is a round glass plate [or plates] carved into

concentric rings, with each ring slightly thinner than the next and

angled slightly differently, focusing the light from a lamp to the

centre and then out over the horizon".

This lightweight set of lenses made possible what could only previously have been done with an enormously heavy and impractically thick lens. Fresnel lenses let lighthouses be seen at night on the horizon, but they have a place in our everyday lives also. Have you ever seen a traffic light, used an overhead projector, seen a car tail light, or used a flat magnifying glass? The Fresnel lens made its debut at Cordouan. Cordouan is

still manned and operated, and still uses a Fresnel lens.

|

| Start Intro Day B25 Part A Index |

| © 2010 - 2013 Daryl May |